They bake with sunshine

Ethiopians may soon be able to bake their own traditional bread, called injera, with help from the sun.

Large parts of Ethiopia today do not have access to electric power or firewood. The results of deforestation are severe. But what if people were given the opportunity to make food without using coal, wood, oil or gas? This can become a reality if students at Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim, Norway succeed in commercializing an oven powered by the sun itself.

The oven has been developed at NTNU with the needs of people in Ethiopia in mind. Asfafaw Haileselassie Tesfay came from Ethiopia to Norway in 2008 to develop a system based on solar power for his home country. He is now very near his goal, which is constructing a solar powered stove that can bake at a temperature of 220⁰C (428⁰F) for 24 hours.

The solar powered stove is the first of its kind and can reach a temperature of 250⁰C (482⁰F), which makes it well suited to Ethiopia’s food traditions and resources.

Solar powered oven

The project started at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in 2007.

Asfafaw Haileselassie Tesfay started working on the project in 2011 and is writing his dissertation based on his work at the Department of Energy and Process Engineering at NTNU.

When the solar powered oven, formally called the storage integrated solar stove, is exposed to sunlight, the heat is transferred to a container with salt chemicals, called the phase change material. The container can store baking temperatures of 220⁰C (428⁰F) for 24 hours and cooking temperatures over 100⁰C (212⁰F) for 48 hours.

The solar stove is constructed out of three parts: A parabolic dish that collects and focuses sunlight, a tube that transfers the concentrated heat and a heat container with a cooking plate.

“This oven has several advantages compared to other solar powered ovens on the market. The biggest difference is that it can reach a high temperature and store that high temperature over time, which makes it perfect for baking ‘injeras’, which most people in Ethiopia eat three times a day,” explains NTNU student Even Sønnik Haug Larsen.

Basic food

Haug Larsen is part of a student team that is trying to commercialize the product. He and his fellow students Mari Hæreid, Sebastian Vendrig and Dag Håkon Haneberg are all from the NTNU School of Entrepreneurship.

For years scientists across the globe have tried to develop solar-powered ovens with different qualities aimed at developing countries. The problem has been that these solutions have not been optimized with the needs of the users, for instance in Ethiopia, in mind. The ovens have not reached high enough temperatures to make injera, and can’t store the heat so that it is possible to make food also in the evenings or at night.

“These solar cookers are only able to boil rice or vegetables and such. But that is not what most Ethiopians eat. They eat injera, a sort of flatbread that needs to be baked. For that you need a temperature of 200-250⁰C (392-482⁰F),” Haug Larsen says.

He adds that he finds it rewarding in itself to make it possible for people in developing countries to make food in an efficient, safe and environmentally safe way any time of day.

“It is exciting to use our technology in practice and show that the product is useful to many people,” Haug Larsen, who is also a teacher, says.

How it works

The solar powered oven is environmentally friendly. When exposed to sunlight the heat is transferred to a container with salt chemicals. There are two working prototypes, one at NTNU and the other in Ethiopia. The need for such an oven is huge, the students have found.

Roughly 50 per cent of the country doesn’t have access to electric power and use fire wood instead, which has accelerated deforestation.

“People hardly have any fire wood or electric power, but they don’t lack for sun,” Haug Larsen says.

In Ethiopia

Haug Larsen travelled to Ethiopia with fellow student Sebastian Vendrig in mid-January to get in touch with customers and potential partners. At the same time they wanted to see if it was possible to produce the oven locally in Mekele, the home city of Asfafaw, the man behind the idea.

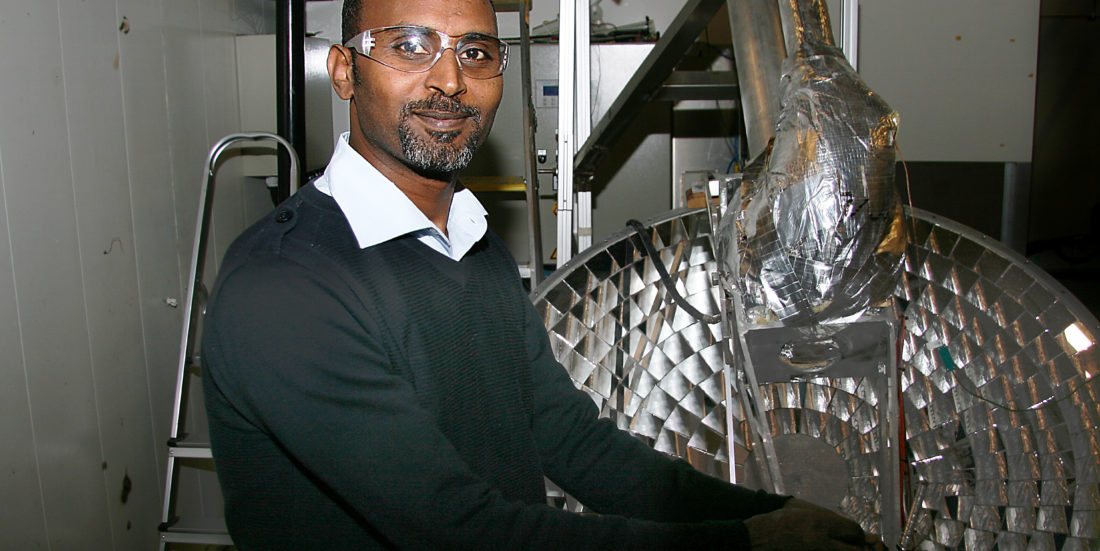

The inventor Asfafaw Tesfay in the process of baking injeras on his solar powered oven. Photo: Dag Håkon Haneberg

“As the users and potential customers are in Ethiopia it is important for us to travel there to meet them and at the same time experience the culture and society. We also want to establish a viable business there and will at the same time look at possible production workshops,” Haug Larsen said before they left.

The students have already been in touch with the Norwegian embassy in Addis Ababa, along with the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) and several organizations willing to help the students.

The project received support from Norfund, Spark NTNU and Trønder Energi. The students are also working with NTNU Technology Transfer (TTO).

Want to expand

The connection between Asfafaw and Ethiopia is the main reason why the group is trying to establish the product here first. The students see a potential market in organizations working in the country, and in schools, universities, hospitals, bakeries, restaurants and hotels.

“It might be possible to make the oven accessible to private people at a later time, but as it is now they have limited funds and will not know how to use it,” says Haug Larsen.

He and the rest of the student group hope to start a business and work with the oven after their studies.

“It would be fantastic if our product could improve the conditions in several developing countries and if we can be part of creating jobs locally,” Haug Larsen says.