Jellyfish invaders: Trondheim Fjord in transition

Jarle Mork has spent the last 40 years of his career studying Trondheim Fjord and its finned inhabitants. Warmer waters and the arrival of new creatures are bad news for the fjord’s cod population, he says. But other fishing practices are problematic, too.

INVASIVE SPECIES: A bulging trawl net, round and fat with its catch, is winched aboard the RV “Gunnerus” research vessel. It’s the summer of 2012, and a video recorded from the bridge by the ship’s captain, Arve Knutsen, shows a crew member walking over to the bottom of the dripping net so he can pull a cord to release the contents onto the deck.

He fumbles a bit in his bulky orange rubber gloves, but then pulls a toggle and quickly backs away. Suddenly, the deck is awash in dark jellyfish, each about the size of slice of bread and the shape of a triangular rain hat. Here and there, a few white bellies of torpedo-shaped fish can be seen among the quivering, glistening mass of jellies.

“I call it the Periphylla splash,” says Jarle Mork, a biology professor emeritus at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. The roughly 1.5 tons in the net, nearly all jellyfish, illustrate a growing and disturbing problem in Trondheim Fjord: an explosion of jellyfish called Periphylla periphylla.

These gooey creatures, some of which can live for 30 years or more, are filling fishermen’s nets and eating zooplankton and small fish that would normally feed the fjord’s traditional top predator, cod.

Mork has spent his entire professional career studying Trondheim Fjord, particularly populations of cod and related species. He now finds himself learning more about Periphylla and just what these creatures are doing to once-healthy fish populations.

The arrival and establishment of Periphylla, combined with changes in the fjord’s water temperature and circulation, are bad news for cod populations and the fjord’s artisanal fishermen, he says.

- You might also like: Bombs away— WWII bombs provide living laboratories for cold-water coral reefs

A good place to be a fish

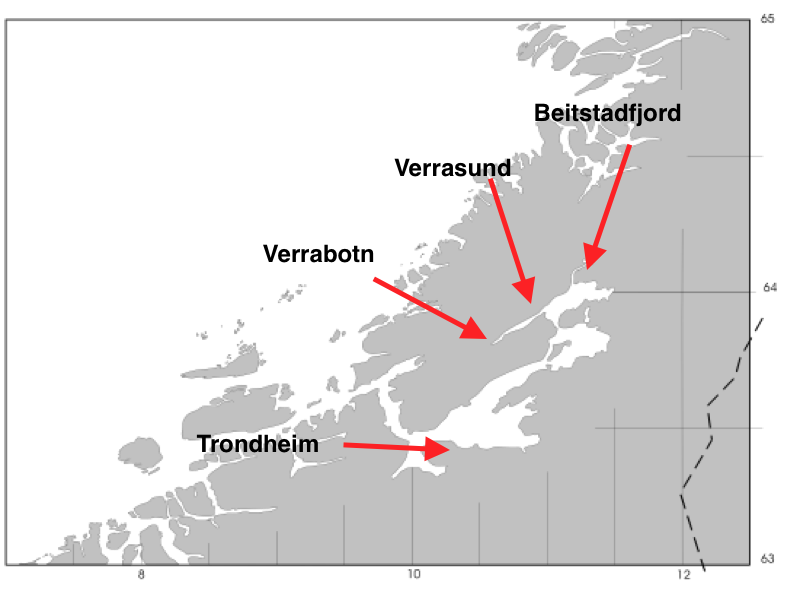

Trondheim Fjord is Norway’s third longest fjord, a complex connected series of “fjordlets” incised into the mid-Norwegian coast. It’s “a good place to be a fish,” Mork says, in part because the fjord’s geographic location makes it suitable for both arctic and boreal species.

As a result, more than 100 fish species call the fjord home. And there’s more: Mork’s genetic research has shown that two of the fjord’s most important fish stocks, cod and herring, have actually evolved to become local populations specifically adapted to the fjord’s conditions.

Trondheim Biological Station, Mork’s workplace for more than 40 years, has been monitoring basic physical and biological conditions in Trondheim Fjord since 1963. By sampling basic physical parameters at different depths and at different times over the year, biologists can put together a surprisingly nuanced picture of what is happening in the fjord. It’s also an important record of how the fjord is changing, especially as the planet warms.

Meticulously maintained over four decades by scientists at NTNU’s Trondhjem Biological Station, funding for the time series stopped for a variety of reasons in 2005. This was “just at the time when significant changes in the ecosystem were taking place,” Mork said. Nevertheless, he said, researchers have added to the time series in more years, although because this funding is associated with different projects, the measurements are more scattered and less systematic than in the past. He hopes that other researchers will continue to add to the time series.

A salty, dense fingerprint

One way in which systematic time series information is useful is by providing scientists with information about where the water in the fjord has come from, based on its temperature and salinity.

Warm, dense, salty water is the fingerprint of the Atlantic Ocean, for example. Combined with periodic fish trawls in specific areas of the fjord, biologists like Mork can see how fish populations change in response to changing seawater parameters.

So it happened beginning in 2000, Mork and his colleagues began to notice the appearance of a gooey dark creature in the routine bottom trawls they did in the different areas of the fjord. This creature was Periphylla.

Periphylla periphylla, sometimes called the helmet jellyfish. Photo: Morten Krogstad, Nord University

While the fjord has always been home to different kinds of jellyfish, Periphylla had all the makings of a disaster. It lives a very long time, reproduces at all times of the year and likes the same kind of food that cod and other fishes eat.

It took just one more factor to turn Periphylla from a potential disaster to a real disaster: Mork calls it the match-mismatch problem.

Perfect timing between predator and prey

Trondheim Fjord’s local stocks of herring and cod have adapted perfectly to both the fjord’s physical conditions and the timing for when different kinds of food are available, particularly for young-of-the-year fish.

Cod, for example, spawn so that their eggs hatch at the right time to be able to eat the larval stages of a zooplankton called Calanus finmarchicus. The young cod’s mouths are too small to allow them to eat full-grown Calanus, which is why they have to eat Calanus larvae, called nauplii. The Calanus population, for its part, booms after the adults feast on big blooms of phytoplankton that occur every spring.

In the decades before climate change began to affect seawater temperatures and circulation, this relationship between cod, Calanus and phytoplankton blooms was well matched. The phytoplankton bloomed and the Calanus population boomed.

The peak of cod spawning occurred at the right time so the cod larvae hatched when Calanus naupliiwere available in huge numbers to feed them.

A mature Calanus, a zooplankton that is important food for many fish species. Immature Calanus are critical food for cod larvae, but are also gobbled up by Periphylla jellyfish, which have invaded Trondheim Fjord. Photo: NTNU

This relationship helped build cod stocks in Trondheim Fjord, and helps explain why the fjord has been one of the most productive fjords on the entire Norwegian coast.

- You might also like: Dark lords, werewolves and Indiana Jones in the polar night

Warmer waters, earlier phytoplankton blooms

As Trondheim Fjord has warmed in recent years, in part due to incursions of warm Atlantic waters, this relationship between cod, Calanus and phytoplankton has changed.

The annual phytoplankton bloom in the spring is initiated by light and water temperatures. Calanus nauplii are hatched and eat the phytoplankton. But for the Calanus to feast on the phytoplankton, the water in the fjord can’t be flushed out of the system too quickly by freshwater run-off in spring.

If climate change modifies the timing of components in this physical framework, a mismatch between the plankton bloom and cod spawning may affect the success of the annual spawning.

Rapid adaption difficult for cod

If something changes the timing of phytoplankton and Calanus booms, cod can’t change their spawning habits as quickly as plankton can — evolution doesn’t work that quickly for fish.

While some cod may spawn earlier by chance, most of the fjord’s cod spawn at the same time as they did in the days before climate change. Unfortunately for the cod, their Calanus prey have already adapted to the warmer waters and mature earlier than they used to.

That means when the cod larvae are on the hunt for Calanus nauplii, most of the nauplii have already grown beyond the size that the tiny cod larvae can eat.

“The rapid change in climate makes adaptation difficult for the cod,” Mork says. “This match-mismatch problem is playing a significant role on our part of the Norwegian coast. During some periods, the change may be so significant that cod and the Calanus come out of phase.”

This mismatch, as it happens, was also perfect for an invader like Periphylla.

A voracious top predator

Periphylla is what biologists call an “opportunistic species,” or one that is able to take advantage of whatever conditions it finds itself in.

“Jellyfish like these have been around for 500 million years,” Mork says. “They have some tricks up their sleeves.”

Jarle Mork surveys a net filled with more than 7 tonnes of Periphylla jellyfish captured from Trondheim Fjord. Photo: NTNU

When Periphylla established a population in Trondheim Fjord around 2000, the local cod stock was weak after several years in a row of low production. The hatching time for cod larvae was less well matched to the plankton bloom, and now the cod had to compete for the right-sized food organisms with lots of Periphylla of all sizes.

Suddenly Periphylla was the population that was booming, in part because they can reproduce at all times of the year. Individuals can live for 30 years or more and so can reach a considerable size. Beyond its very young stages, Periphylla has no natural enemies in the fjord.

A dense Periphylla population can effectively vacuum the water of nauplii and other plankton and leave little for cod larvae and for more mature fish. Periphylla also do more than just eat Calanus and other cod food: they eat the cod larvae and other young, small fish, too.

“They are very efficient predators,” Mork said. And now, in the innermost parts of Trondheim Fjord, they have replaced cod as the top predator.

- You might also like: The next chapter in Norway’s history is to conquer the oceans

Seven to eight tonnes in five minutes work

Now, when Mork goes out on one of his periodic trawls, in certain part of the fjord he can catch 7-8 tonnes of Periphylla in a 5-minute trawl. The worst affected is Verrabotn, in inner Trondheim Fjord.

Mork says Verrabotn acts like a “trap” for Periphylla. Local current systems that are timed with the jelly’s daily movements up and down in the water column carry it into the farthest reaches of Trondheim Fjord and allow it to accumulate there. Since 2008, biologists estimate that there may be upwards of 20000 tonnes of Periphylla in the innermost part of the fjord.

There are so many jellyfish in this area that there is simply not enough food for them, and in some years, there are mass die-offs in the winter, Mork said.

Finding options for local fishermen

The timing of the Periphylla invasion couldn’t have been worse for Trondheim Fjord’s local artisanal fishermen. Since 2000, when Periphylla first arrived and Trondheim Fjord’s water temperatures began to increase, the percentage of cod in a fisherman’s take has dropped by 60 per cent, Mork says.

Part of this is because of Periphylla, and part of this is due to the fact that species such as pollack, European hake and saithe have thrived in warmer waters, so they make up a greater percentage of a fisherman’s take. However, at the same time, prices for cod began to drop, making it even more difficult to make a living from fishing for cod.

Artisanal fishers in Trondheim Fjord face the real possibility that their nets will fill with Periphylla jellyfish instead of with cod or herring, which have made up the traditional fishery in the fjord. Photo: Courtesy SINTEF/NTNU JANUS project

In 2012, Mork joined a coalition of biologists and social scientists from NTNU and SINTEF to work on the three-year-long JANUS project, funded by the Research Council of Norway and designed to look at options and future scenarios for the Trondheim Fjord fishing community in response to the Periphylla invasion and other changes more generally.

As part of this research, Mork and other researchers conducted workshops and interviews with local fishermen affected by the invasion, to find out what fishermen themselves thought and felt they needed.

Using jellyfish as a source of collagen

One possible response to the Periphylla invasion that the JANUS project explored was to stop fighting the inevitable: Instead of seeing Periphylla as a pest, treat it like a resource. Periphylla could be a potential source of collagen, used in cosmetics and the pharmaceutical industry.

That, as it turned out, wasn’t seen as such a good idea, said Jennifer Bailey, a professor in the Department of Sociology and Political Science, who was part of the JANUS project.

Essentially, she said, if you were to shift fishermen to harvesting jellyfish, then resource managers are in the uncomfortable position of having to manage and protect an invasive species.

“Do you really want to maintain a stock of jellyfish, which is more of a nuisance species?” she said.

Purse seiners a bigger threat

The interviews the JANUS researchers conducted with professional fishers in Trondheim Fjord also showed that they really didn’t want to start focusing their catch on the gooey, stinging jellyfish.

“They would really have to change their behaviour” to catch and handle jellyfish as a target species, Bailey said. “What we found is that they didn’t necessarily want to maximize their profits. What they really wanted was a reasonable lifestyle and for their profession to be able to continue.”

The Trondheim artisanal fishery isn’t big, but until the invasion of the Periphylla jellyfish, was dominated by herring and cod. Photo: Thinkstock

In that respect, the interviews with the fishers in Trondheim Fjord turned up another, less-than-obvious problem.

Current Norwegian fisheries management policy allows larger fishing vessels to come into Trondheim Fjord to use up their fleet’s fishing quotas if those quotas haven’t been reached elsewhere.

That policy means that big boats that use purse seines, big long nets that basically catch everything in their way, could come into Trondheim Fjord and “vacuum the fjord of fish,” the fishers told the researchers.

This, the fishers said, was far worse than jellyfish.

- You might also like: Trashing the ocean

A look into the future

There are not many full time professional fishers left in Trondheim Fjord, and for them, shifting away from the inner areas of the fjord that are dominated by Periphylla makes sense.

Still, outer parts of the fjord continue to host good populations of fish, Mork said. Recent bottom trawl catches in Stjørdalsfjord, one of the outermost parts of Trondheim Fjord, showed no Periphylla and a diversity of fish species that was similar to that found in the inner parts of the fjord before it was invaded by Periphylla.

Mork says climate change will continue to alter ocean temperatures, which will make for significant changes traditional fisheries in the northeast Atlantic and in Trondheim Fjord. Some will stop fishing.

“The current problems with jellyfish blooms and reductions in cod stocks in the inner fjord have certainly reduced the number of active fishermen there,” he said. Now, the remaining fishers have to rely on additional income from a crab and crayfish fishery and blue mussel farming, he said.

“These changes are not uncommon for fishers, who have always adapted to changes,” he said.

But the lesson of the JANUS project is also clear, he added.

“In the end, fish prices and annual vessel quotas are still important in determining the viability of artisanal fisheries in Norway,” he said.