Do elite sports promote doping?

The pursuit by elite sports of media — and the public’s — attention generates hardcore competition that even highly trained bodies can barely handle. Some athletes find doping to be their only recourse.

The use of saline solution, nebulizers and asthma medicine among Norwegian nordic ski stars has heated up the debate in Norwegian sports circles over doping. These “treatments” are within legal bounds, but critics argue that by using them, the Norwegian cross-country team is operating in a gray area.

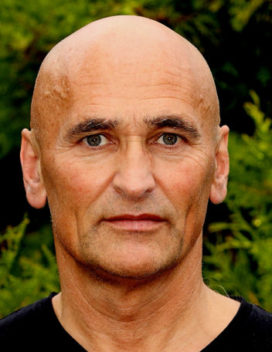

Harry Arne Solberg is a professor of Sport Management/Sports Economics at NTNU’s Trondheim Business School

Harry Arne Solberg is a professor of Sport Management/Sports Economics at NTNU’s Trondheim Business School. He believes that the battle for revenue is changing sports so that they attract a wider audience.

“This focus is pushing the boundaries related to the use of illegal substances. As an athlete, you’ll fall behind if you can’t keep up,” he says.

- You might also like: NTNU to help Team Sky suit up

Creating impressive competitions

In elite sports, sponsors mean money, money is power and the media powers it all. If sports are successful at getting media coverage, the sponsors will come.

To win over the market, various sports are being made more audience friendly. Nordic skiing has implemented mass starts, and the organizers of the Tour de Ski use cycling’s Tour de France model: a long, continuous period of grueling competition. To win the overall event, the athlete needs to dominate all the stages – the long as well as the short ones and the steep as well as the flat sections.

In addition, multiple competitions within the larger competition mean that athletes are also vying to win individual stages. This increases public interest among nations that do not have athletes in the running for the overall win.

Opposing aims collide

“The fight for viewers creates an extraordinary situation. The medical profession argues that the human body isn’t designed for grueling stages every day for weeks on end. Doctors have recommended reducing the length of the three biggest bike races – the Tour de France, Giro de Italia and Spain Around – from three to two weeks, but organizers refuse to do this,” says Solberg.

He points out that cross-country skiing is now trying to copy this form of competition in the Tour de Ski, and last winter a similar competition was launched in Canada.

“In the early years of the Tour de Ski, several athletes became sick. The advantages of doping in ‘inhumane’ competitions like this are greater, partly because there isn’t enough time and space to rest. When sports resort to events that “foster” doping this way, opposing aims collide. To put it bluntly, we can say that the anti-doping work is a form of indulgence. One hand has to clean up the damages the other hand has created,” he says.

He also points out that the traditional sport of ski jumping has undergone a transformation in order to attract more viewers. The hills have steadily increased in size. The ski jumping world record distance in the 1970s was around 150 metres. Today top competitors are flying 100 metres further.

- You might also like: Suit seams affect speed

White elephants remain

Solberg says that sporting events constitute a large part of investments made in sports. When countries and cities compete for prestigious events it’s easy for the IOC, FIFA and UEFA to set high standards for facilities, without regard for how much a new, modern facility costs. The result is often that the project exceeds the original budget – and when the event is over, the country or city is left with a “white elephant”.

By this Solberg means the huge sports facilities that are built for individual events, which subsequently cost more to run and maintain than they clear in terms of money or benefit.

“Often people have naive expectations of what these events will provide afterwards” in the way of benefits,” says Solberg. “South Africa had planned to upgrade an existing football field in a slum area of Cape Town for the 2010 football World Cup. But FIFA wanted to have a new football court – and this started the ball rolling. FIFA was joined by local actors who pressured the government, and today the city has been left with a white elephant of a stadium that’s enormously expensive to maintain, and that has a capacity of 65,000 for a local team that draws around 6,000 spectators,” he says.

Many former event organizers are struggling with the same thing, including Korea and Japan after the 2002 FIFA World Cup, Portugal after the UEFA European Championship in 2004, and even football nation Brazil after the 2010 World Cup.

Sponsors withdraw support

In elite sports, money rules the game, while market forces can help curb the use of illegal substances.

“For example, German television channels didn’t want to air the Tour de France, because of all the doping scandals. The Tour de France is the biggest of all the cycling championships, and it’s owned by a commercial entity, Amaury Sport Organisation (ASO). It’s been claimed that ASO has worked harder to combat doping than the International Cycling Union,” says Solberg.

Solberg says doctors have recommended reducing the length of the three biggest bike races – the Tour de France, Giro de Italia and Spain Around – from three to two weeks, but organizers refused. Illustration photo: Thinkstock

No sponsors want to be associated with doping. When sponsors withdraw their support, it affects profits.

Solberg finds it worrisome that the Norwegian Ski Federation has kept the Martin Johnsrud Sundby doping case secret from a new sponsor. He says, “The Ski Federation has tackled the issue in a way that doesn’t inspire confidence. It’s also troubling that FIS has gone ahead and is compensating Sundby for the prize money he has to pay back after being banned for violating doping rules. It sends a negative message.”

Systematic cheating not suspected

Arve Hjelseth, associate professor in the Sociology of Sport at NTNU, believes FIS lost face in the Sundby case because it looks as if someone has tried to disguise the truth.

He points out that cross-country skiing has strong symbolic value for Norwegians, and that people need to be able to trust that athletes and their coaches aren’t pushing the rule limits of illegal drug use.

“In the Sundby case, boundaries appear to have been pushed. Despite the several Norwegian doping cases, I still don’t believe that systematic and organized doping among Norwegian cross-country skiers is going on, or that our nordic skiers can get away with doping without the support network knowing it,” says Hjelseth.

Critical journalism

Hjelseth noted that Norwegian cross-country athletes have seldom wanted to develop their own training programme since Norway’s Elite Sports Centre was established. If someone has been doping systematically, doctors, support staff and management would know it. If this happened, it would topple the Norwegian top sports model.

However, he believes that the debate about power relationships and resource use in represents a relatively new twist to the world of sports that it has lived without up to now.

“The journalists who took the risk to examine whether more was going on under the surface when the Sundby affair became known, soon found something. Recently, the media has begun to show interest in sports politics to a greater extent than previously. This is a new reality that elite sports will have to learn to live with,” Hjelseth said

Photo captions:

Harry Arne Solberg is a professor of Sport Management/Sports Economics at NTNU’s Trondheim Business School.

Solberg says doctors have recommended reducing the length of the three biggest bike races – the Tour de France, Giro de Italia and Spain Around – from three to two weeks, but organizers refused. Illfoto: Thinkstock