Indulgence trading was big business before the Reformation

The way to shorten one’s time in purgatory was to obtain indulgences. But they had to be purchased, so only people who were well off could afford them.

Purgatory was a feared place. People who paid for indulgences could reduce their time there. Illustration photo: Thinkstock

Purgatory was a feared place in the Middle Ages. According to Catholic doctrine, going through the state of purgatory on the way to heaven was a purification process to cleanse oneself of sin.

“Purgatory was a terrible place. To speed up your time there, you could buy indulgences. The Bishop decided on and issued the indulgences,” says archaeologist Birgitta Berglund at the NTNU University Museum.

Recently she talked about the subject on the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation’s documentary and reality TV series Anno.

Reserved for the rich

When Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses to the church door in Wittenberg 500 years ago, it was the sale of indulgences he was most opposed to. Trading in indulgences was big business before the Reformation. Buying indulgences was expensive and thus reserved for the rich, who had the money to buy them or to go on a pilgrimage to Rome or Santiago del Compostela.

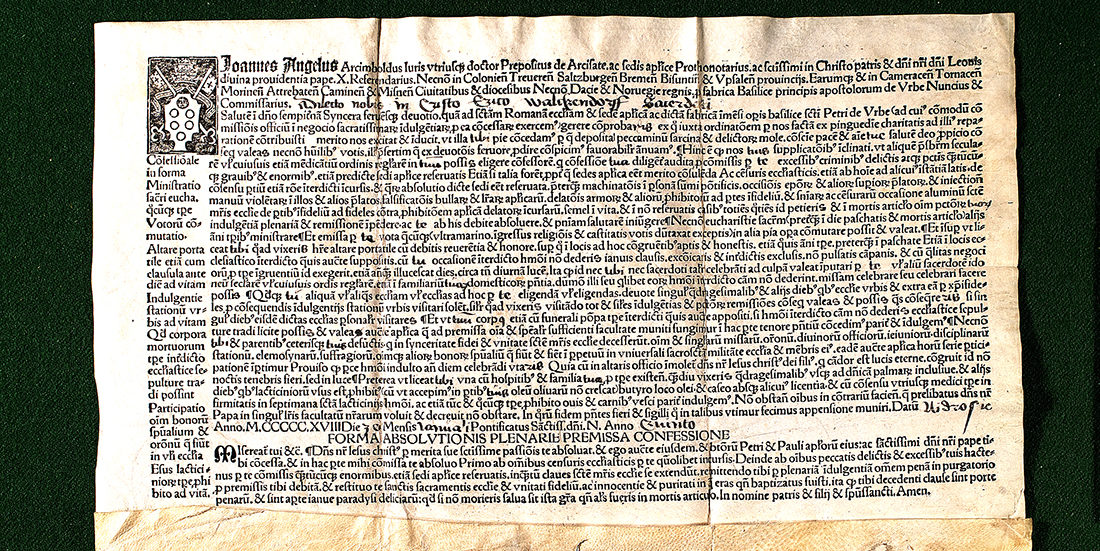

This seal was attached to a letter of indulgence issued to Erik Walkendorf. Photo: National Archives, Oslo

In the early 1500s commissioners travelled around and peddled indulgences.

“With the advent of the Reformation, indulgences and purgatory disappeared. Just believing was sufficient to make it to heaven, and the need to do penance fell away,” says Berglund.

Indulgences for St. Peter’s Basilica

The archaeologist became interested in indulgences during excavations in the yard at Alstahaug vicarage in Helgeland, where Petter Dass worked as a priest over 300 years ago.

In the 1960s, archaeologists excavated under the floor of the old nave in Alstahaug church. When Berglund went through the grave findings from that time, she found a wax seal in a small silver case. A letter of indulgence had been attached to the seal. The case was found next to the head of a 35-year-old woman in one of the tombs under the church floor from the 1500s.

“On the wax seal you can see St. Peter with a halo and the key to the kingdom of heaven. The text ‘SIGILLUM FABRICE BASILICE SANCTI PETRI DE URBE’ is imprinted on the seal, showing that the letter of indulgence and the seal were sold to raise money to build St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome,” explains Berglund.

Arcimboldus’ seal

Wax seal in a case from a woman’s tomb under the church floor in Alstahaug church. Photo: Per E. Fredriksen, NTNU University Museum

It turned out that the seal was identical to another seal issued to Erik Walkendorf in Nidaros, dated 1518. The seal was in a brass capsule, and was found on a letter of indulgence.

The lower half of both seals shows a shield with a diagonal band with three stars, framed by a cardinal’s hat with hanging tassels. This was the seal of the papal legate Johannes Angelus Arcimboldus. Arcimboldus was responsible for the sale of indulgences in Germany and large parts of the Nordic region. The letter from Alstahaug is not preserved, but what was issued to Erik Walkendorf shows that it was a printed text with space to write in the name.

“Indulgences letters were also important for Gutenberg and the development of the printing press,” said Berglund.

But how did Arcimboldus’ seal of Nidaros end up under a church floor in Alstahaug?

Unofficial priest’s wife

On the underside of the case that held the seal stamp found in Alstahaug were three holes and the remnants of a string. The string had been threaded through the holes for attaching the case to the indulgences letter. Photo: Per E. Fredriksen, NTNU University Museum

At this time Alstahaug parish was a canon debt. That meant that the priest served at Nidaros Cathedral, and was obliged to do priestly work in Alstahaug, the vocational calling that provided his income.

“I assume he bought the letter of indulgence when he worked in Nidaros Cathedral,” said Berglund.

Women priests were unthinkable in the Middle Ages, and priests were also not allowed to marry. So it is strange that the unknown woman under the church floor had a letter of indulgence. But Berglund has a theory.

“We don’t know who she was, but we do know that individuals who were buried under the church floor were of higher rank. Since priests couldn’t marry, she wasn’t an official vicar’s wife. I think she was a woman who had sinned with the priest,” she says.

In the Iron Age and Viking times, it was common for the dead to be buried with objects by their side. This was not the case in the Christian era, with the exception of religious symbols.

“I think the priest gave the letter of indulgence to her so that her time in purgatory would be shorter,” says Berglund.