Real men dance the minuet

The Birken ski festival, the Great Trial of Strength cycling event and the Norseman Xtreme Triathlon are considered to be real tests of manhood today. But a few hundred years ago, the minuet was how men displayed their skills and strength.

We’re going to take a trip back in time to when the masculine virtues consisted of fencing, riding – and dancing the minuet. We’re not talking about a dandy who cruised around to all the society balls in silk stockings and powdered wigs to charm the ladies. No, these were important qualities to cultivate for men who attended the Royal Military Mathematical School, now the Norwegian Military Academy, the men who would become officers and lead the troops in war – or conduct negotiations to avoid war.

The complex techniques of the minuet exercised their balance and agility, and the men learned the necessary etiquette and correct demeanour to conduct themselves properly in society and to build networks in influential circles. A man who could dance well radiated authority and could impress others.

PhD candidate Elizabeth Svarstad at NTNU’s Department of Music has written her doctoral dissertation on the topic of “dance as social education” and focuses on dance in Norway from 1750 to 1820.

Elizabeth Svarstad with the special manuscript she found in the Gunnerus Library.

Photo: Idun Haugan / NTNU

“We didn’t know that the minuet was so important for a person’s cultural upbringing. Dance taught etiquette, built strength, balance and coordination, and developed good posture and proper conduct. Dance instruction in military education was emphasized as good training for military exercises,” Svarstad says.

Dance training was an important part of shaping the young cadet’s bodies, and they attended compulsory dance classes several hours a week. Records in the Norwegian military archives state that dance helps to “improve what is raw and rough in our young bodies.”

In the Sun King’s court

Our travel in time goes back to the 17th century, to the period when Louis XIV reigned in France and wielded great power and influence throughout Europe. The Sun King and his court set the standard of etiquette and new trends in Europe’s higher social echelons.

In addition to being a megalomaniac and a warmonger, Louis XIV was also an eager dancer. He created the Académie Royale de Danse (Royal Dance Academy) in 1661, for which twelve ballet masters developed an innovative new style called belle danse. The minuet was part of this dance style.

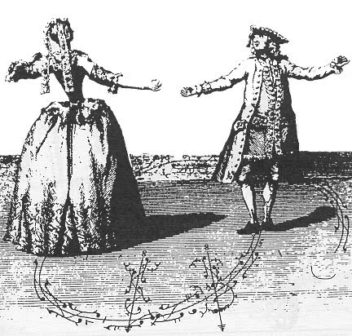

“For a long time, the minuet was ballet’s first dance. It’s a dance that one couple at a time performs, and the standard court minuet consists mainly of small steps in different directions,” says Svarstad. “The steps contain elements from the rest of the French dance style, such as being on the ball of the foot (quarter pointe), bends and rises in the knees and small elegant jumps. The steps involve intricate footwork that requires lots of practice while keeping the body straight, controlled and elegant.”

This dance technique helped to form the basis of classical ballet. Concepts and names of moves from this period are still used in today’s ballet technique. The dance masters determined the correct execution of the steps, and dances were often recorded in notated dance scores. They consist of characters and symbols that illustrate the dance movements and steps so that the choreography can be read and understood.

Found gold in the archives

Norway’s nobility was also keen to learn how to dance and conduct itself in the technically demanding minuet. Children of “finer” families were sent to dance classes with travelling dance masters – or better yet, the dance masters were hired to instruct pupils in private homes, often several times a week. Painstaking instruction and training were required to learn this complicated dance.

Svarstad combed libraries and delved into documents that might tell about dance in Norway at this time. Together with her supervisor, Professor Anne Fiskvik at NTNU, she discovered a unique manuscript in the Gunnerus Library in Trondheim.

Numerous people had looked at the manuscript before, but nobody correctly understood its importance. A trained eye and special skills are needed to understand what is written on the fragile, yellowed paper pages with their ornate, quickly written handwriting and strange symbols.

“This is a gold mine! When I saw it, I immediately realized that it described parts of a minuet, written in Feuillet notation, which originated with the dance master Raoul-Auger Feuillet. He was one of the great dance masters at the court of Louis XIV,” says Svarstad.

Feuillet published textbooks in dance notation as well as several collections of ballroom and theatrical dance choreographies. More than 450 preserved choreographies from the 18th century have survived, composed by different dance masters. Many of them used Feuillet’s notation system. Pierre Beauchamp, Louis XIV’s personal dance master, is actually credited with devising this system, but Feuillet described the system in detail, making it available to others.

According to Svarstad, notated dance scores are a key source of information for dance researchers and practitioners of Baroque dance. They allow dances to be reconstructed more accurately than through more ambiguous textual descriptions. Feuillet notation shows the dance steps and the how the dancers move around the room, as well as the relationships between the dance partners and between the dance and the music.

Travelled from Versailles

The dance documentation that has been reviewed in Norway and the Nordic region to date has not provided much information about the minuet dance form – making this particular manuscript especially important in the dance context. Dance books from the 1700s mainly contain descriptions of the widespread contra dance form.

“We’ve assumed that people were dancing the minuet in Norway in the 1700s, but very few sources say anything about how it was practiced. This document shows that the reach of the Sun King’s court minuet also extended all the way up to Norway,” says Svarstad.

She notes that through her PhD work she has charted a lot of the repertoire found in Norway.

“What is so special about this manuscript is that it contains detailed information about the minuet, and that the information about how it was danced corresponds to European practice. Finding this Feuillet notation is important and unique in Norway, and for the whole Nordic region, as far as I know,” she says.

Deciphered the codes

Christoffer Blix Hammer, a civil servant, scientist and author from Hadeland in south-eastern Norway, recorded the dance notation in the 18th century. He bequeathed his extensive collection of books and documents to the Royal Norwegian Society of Sciences and Letters, and the collection is now part of the Gunnerus Library.

Hammer clearly spent time with a dance master, probably at Sorø Academy in Denmark, to learn or to fine-tune his practice of the minuet. His notes from the dance instruction show how important it was to be able to conduct oneself on the dance floor for a man in his position. Hammer’s hasty pen strokes recorded the steps and movements, in order to memorize them and bring them to Norway.

Svarstad recognized the dance symbols because she had studied Feuillet notation and 18th century French dance sources for years. In addition to being a dance researcher, she is a dance artist and teacher specializing in historical dances. She is very familiar with what the different symbols mean, and is probably the only person in Norway with this in-depth knowledge. Even so, the text posed some challenges.

“When I started, the words were totally unintelligible, but with a bit of help from experts in Gothic handwriting to get me started, the words became decipherable,” says Svarstad.

The seven fragile sheets were also in the wrong order, which didn’t help to clarify their meaning and transcription.

“I’ve been working on the manuscript for a long time and have studied Hammers handwriting in detail. But even with the help of writing experts, it’s ultimately my dance background that has enabled me to transcribe the text. You have to be familiar with French 18th-century dance technique, plus Norwegian and French dance terminology, to fully understand the content of the document,” she says.

International significance

The Feuillet notation is special not only because it was found in Norway for the first time, but also because the manuscript contains several drawings that probably haven’t been found anywhere else. This gives the document international significance.

Among other things, the notation in the manuscript shows the five positions of the feet, which we still know today from classical ballet. One drawing depicts how the turnout in the hips can be trained using an apparatus where the feet were fastened and turned outward. Some of the drawings show the minuet’s figures and the dancers’ placement in relation to each other, including the Z-figure characteristic of the minuet. Two drawings also illustrate how the student can practice the minuet footwork by walking in a circle, either forward or sideways. Several of these notations are special in the European context.

Tilden Russell, a recognized professor of dance history at Southern Connecticut State University, says that this manuscript is unique.

“While many 19th century manuscripts with dance choreographies have survived, it’s really rare to find personal notebooks with sketches and notes. This is especially true of the Hammer manuscript, which contains a student’s notes from his lessons with dance master M. Dulondel. This manuscript may be the only one of its kind,” says Russell.

He points out the diagrams showing how the Z-figure was performed and the diagram of the wooden box designed to train the turnout as the document’s most remarkable features.

Taking off one’s hat

The text in the document even describes how to greet someone and take off one’s hat in a fashionable and elegant way: in a clean line in three movements, then turning the hat towards oneself. The text also includes descriptions like ” when dancing one must hold the body in a straight perpendicular line” and “hold your fingers apart one below the other” in carrying out the dance.

As Svarstad explains, each movement needed to be practiced carefully and conveyed with elegance and confidence. Greeting each other was an essential part of society life. You can find descriptions of specific greetings for any given situation in many European dance manuals. “You greet people differently, depending on whether you’re entering a room, walking, meeting a person, inviting someone to dance, after the dance, bringing a lady back to her seat, handing someone a snuff box or leaving a room,” she says. And these are just a few examples of greeting etiquette.

Out the door

For almost 150 years, people danced the minuet in many parts of Europe. The dance was an integral part of the culture and society life of the nobility.

But then, along came the French Revolution, and everything that symbolized the aristocracy was discarded, including the minuet. The dance represented traditions and an era that the French people wanted to get rid of. The Revolution imposed the death sentence on the minuet in 1789.

But far from dying out, says Svarstad, “the dance masters held on to the minuet and included it in their teaching repertoire into the 19th century. They travelled around and ran dance schools in the largest cities in Norway. Ads for dance lessons can be found in Adresseavisen, Norway’s oldest daily newspaper, as late as the 1890s.”

The reason the minuet maintained its popularity was because it was considered so important for proper upbringing and good attitude.