Do archaeologists have to dig to uncover the mysteries of the past?

Which method works best for archaeologists when surveying an area? In the case of a recent archaeological survey in Halden municipality, georadar turned out to be good enough to discover a Viking ship.

Archaeology is exciting and gives us glimpses into the past. But it is also expensive and can be time consuming.

Ground penetrating radar (GPR or georadar)

- NIKU used a georadar system in Dilling, manufactured by Malå in Sweden. NIKU and the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute in Vienna, Austria collaborated to customize the system.

- The NTNU University Museum carried out georadar on Øya in Trøndelag county, using a Norwegian-developed georadar system manufactured by the 3D-Radar company. This radar system originated in Egil Eide's NTNU doctoral dissertation and was published almost 15 years ago. The system has since been updated and improved.

Many possible area wait a long time to be investigated, if ever. So, the possibility of using a gentle method that is cheaper and takes less time is certainly enticing.

The traditional method of mapping a site is excavation. Archaeologists mechanically remove the topsoil from parts of the exploration area as gently as is practically possible to create test trenches. If they find anything interesting, they can expand the investigation.

But in recent years, archaeologists have had access to another method. A recent report compares the methods.

- You might also like: Thousand-year-old cathedral reveals its secrets, stone by stone

Is georadar good enough?

Georadar (also called ground-penetrating radar, or GPR) sends electromagnetic signals into the ground. This works almost like echo sounding, but on land. By measuring both the time it takes before signals are reflected and the strength of the signals, georadar generates a kind of map of different features at various depths underground.

Øya, an area in the town of Melhus where the NTNU University Museum is investigating an archaeological excavation site. Before beginning to unearth large areas, it’s important to study the site and where to dig. Photo: Silje Fretheim, NTNU

This method is obviously much more gentle than digging up the site. You don’t risk damaging what may be there, and it’s much faster. You can map large areas in a short amount of time. Georadar is also cheaper.

“Archaeological surveys are also a requirement in the Norwegian Cultural Heritage Act, and can show up in connection with planning matters and development issues. People who want to use an area often have to pay for these surveys,” says archaeologist Lars Gustavsen at the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU).

Georadar investigations figured prominently in the recent discovery of a Viking ship and several long houses in Halden municipality.

But is georadar always good enough?

Archaeologists from NTNU and NIKU decided to find out. With money from the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage (Riksantikvaren), they used both methods at two sites, one at Øya in Melhus in Trøndelag county and one in Dilling in Østfold county, according to the Norwegian archaeological website Norark.

These two sites had already been systematically investigated by the county councils and were places where archaeological excavations were to be conducted.

“This made it possible to compare the way county councils usually conduct archaeological site evaluations on cultivated land, known as test trenching, with the results of large-scale geophysical investigations,” says researcher Arne Anderson Stamnes at the NTNU University Museum.

Excavation scope narrowed

At Dilling, the total area was around 8 hectares, or 80 000 square metres. It was clearly not practical, desirable or economically feasible to excavate an entire area of that size. To do that, you would need to know that something special is buried there.

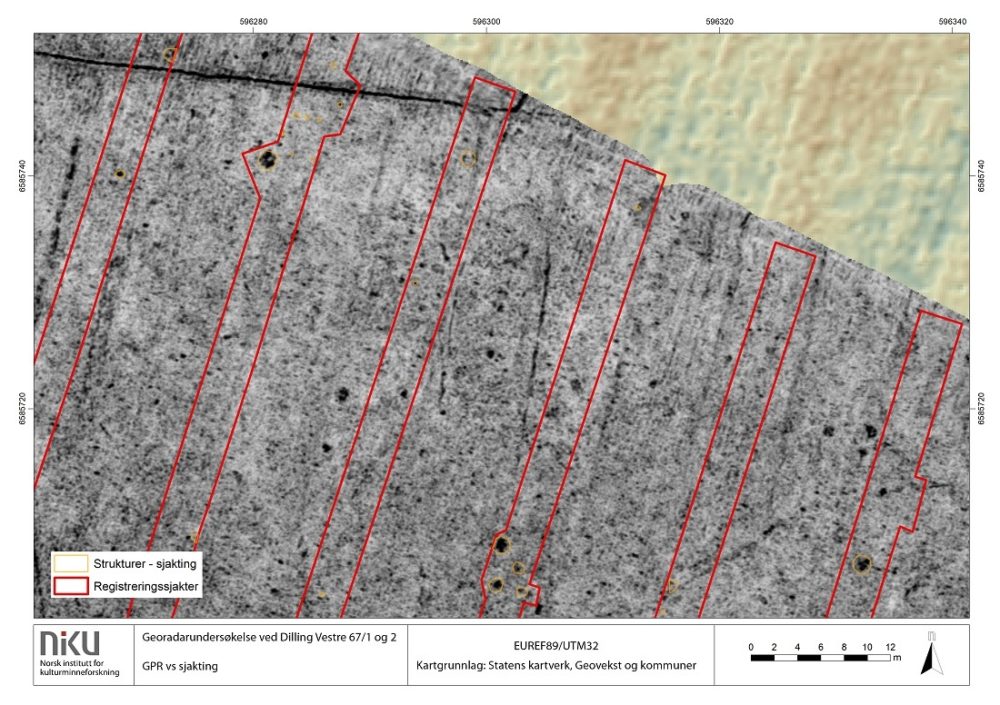

NIKU conducted georadar surveys on just over half of the site, around 4.5 hectares. Later, the Cultural History Museum did a test-trenching excavation on close to 3 hectares, where they found 115 buildings from the Early Iron Age, divided into four residential areas during the excavation. In addition, they found graves, cooking pits, fireplaces and more.

At Øya in Melhus, the exploration area was close to 3.5 hectares. The NTNU University Museum test trenched just over 2 hectares of this area. They found 150 cooking pits, a long house and possible graves or grass drying areas for winter feed.

- You might also like: Iron-age Norwegians liked their bling

Results

At Dilling, the excavation revealed 39 per cent of the artefacts that were later dug out, while georadar only found 6 per cent at first glance. However, this may be due to the fact that interpreting the data requires recognizing patterns that have archaeological meaning. The geophysical information has to be translated into an archaeological interpretation. A direct comparison of the georadar results and the actual excavated findings revealed 18 per cent of the features.

The georadar generated enough finds to provide a basis for further investigations. Excavating gives better results for a more limited part of an exploration site, and georadar results are best for larger areas.

At Øya in Melhus, archaeologists detected 29 per cent of the archaeological features by excavating. Using georadar, they found only 10 per cent of them. But afterwards it was clear that 23 per cent of the features were visible in the georadar data.

Both research areas revealed small or shallow features, such as postholes, that were difficult to detect using georadar. However, the detection rate for larger features, like cooking areas and fireplaces, was as high as in the excavations.

Article continues below photo.

Archaeologists were able to compare both methods. These images are from the georadar used in Dilling. Photo: NIKU

Both methods useful

The conclusion by the archaeologists was that both methods are needed, because each of them is useful in specific areas.

Excavating gives the best results in a limited area. Excavation also makes it possible to date samples of what is found.

Georadar provides data that is useful for avoiding expensive surprises, and for studying as much as practically possible of the area being evaluated. Georadar gives a clear impression of what’s in the ground and helps to avoid having surprises pop up.

Georadar also supplies information that may be relevant to others, such as geological and geotechnical information, drainage maps, cables and pipes and the like. In other words, by including georadar early in a project, it can provide an economy of scale beyond the archaeological information.

Article continues under photo.

The idea that georadar is a new, unfamiliar and immature technology is not entirely correct. This photo was taken at Øya in Melhus. Photo: Arne Anderson Stamnes, NTNU University Museum

Georadar is getting better

Many archaeologists still consider radar a new, unfamiliar and young technology, and some are sceptical of whether it yields as good results as excavation.

But the technology and its use have improved in recent years.

“In fact, since 2008 the number of archaeological georadar surveys carried out annually in Norway has quadrupled. At the same time, the number of surveys conducted for administrative purposes, not just research, has seen almost a tenfold increase. The idea that this is something new, unfamiliar and immature is therefore not entirely correct,” says Anderson Stamnes.

“Archaeologists also need practice in interpreting the data provided by georadar, which is one reason why the results of a research project like this are so necessary. We need more examples of the possibilities and limitations of the various archaeological methods,” he says.

In these two examples, georadar was not as effective in detecting certain types of cultural features as excavating was. Small features with relatively low contrast are particularly difficult to detect. Postholes are a typical feature of this type.

But excavation can also yield the wrong result, if you’re mistaken about what you’re looking for. Using georadar to provide a good knowledge of the whole area is then especially useful.

Both methods are able to detect fireplaces, cooking pits and ovens and to delimit evaluation sites about equally well.

Source: Arne Anderson Stamnes (NTNU University Museum), Lars Gustavsen (NIKU). Avgrensning av arkeologiske kulturminner i dyrkamark. Metodevalg og forvaltningsimplikasjoner. (Delimiting archaeological sites in cultivated land. Method selection and administrative implications.)