Stone phalluses and ancient fertility cults

Fertility cults were common throughout Europe in pre-Christian times, and Norway also still has signs of them.

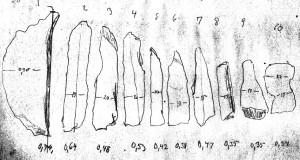

Close to one hundred stone phalluses have been found in Norway. They are symbolic representations of the penis, representing male potency and fertility. Animal and human sacrifices made to a symbolic phallus were thought to ensure a successful new crop among people, animals and nature. Ancient fertility rituals have survived in modified form into the modern era.

Elven sacrifice “alveblot”

The pagan sacrificial ritual and harvest festival held at the winter solstice in the old Norse month of Ýlir was also the time for the alveblot, or sacrifices to the elves.

Elves played a central role in pagan cult ceremonies. They belonged to the Norse pantheon, but were closer to people’s earthly life than the gods. The elves embodied both fertility and death powers.

Elf cult ceremonies were usually local and happened within each household, but they were also celebrated officially at certain times of the year, such as at the winter solstice on December 21st. At this time of year nature lay dormant, and this was therefore a feast for the dead, but it also looked ahead with hope toward a fertile year for people and livestock.

In the skaldic poem Austfararviser (“East Journey Verses”) King Olav Haraldsson’s court poet Sigvat Tordarson tells the story of how he once was refused entry to a home where the alveblot celebration was well underway. Strangers were not welcomed. Sigvat describes a woman’s voice shouting: “Do not come closer, you godless wretch. I fear Odin’s wrath, we worship the ancient gods!” The woman was preparing for the alveblot, during which the phallus played a meaningful role.

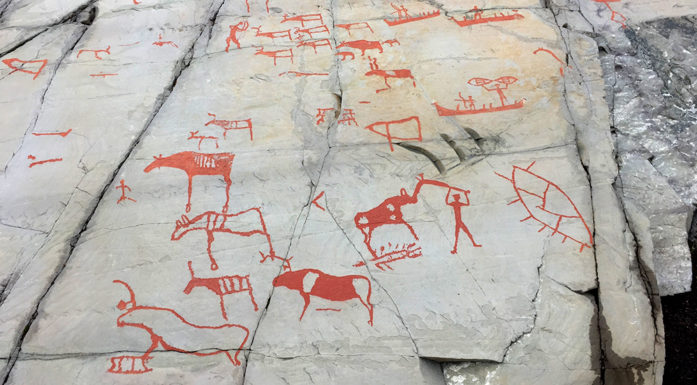

We know little about how the original rituals took place in the Nordic regions, but texts and images from Mediterranean countries show how parts of this cult were performed. Soil fertility and the rebirth of nature were personified through dance and sacred drama, as in the myth of Persephone, where her mother Demeter looks for her daughter who has been abducted to Hades. Myths such as this symbolize birth, death and rebirth of vegetation.

The fertility god Priapus

A Greek myth explains the background to phallus worship: Aphrodite, the goddess of love, gave birth to a child, the glorious deity Priapus. The father’s identity was uncertain, but Zeus himself was suspected by his wife Hera.

With a magical touch of her stomach, Aphrodite cursed the child that grew there. That led to the child, Priapus, being born ugly, with a huge body and a giant, permanent erection.

Aphrodite was so repulsed by the obscenity of this creature that she threw him out of her kingdom and abandoned him in the wilderness.

Here Priapus was taken in by a shepherd who saw that wherever this creature walked, everything grew vigorously. Plants sprang up from the ground and the animals jumped on each other, mated violently and multiplied. Priapus soon became known and worshiped as a fertility god.

The story of Völsa

The Scandinavian story of Völsa þáttr (þáttr, ‘short story’) paints a vivid picture of how a phallic ritual was performed.

The story was recorded in the 1380s. The action took place in 1029 and shows that pagan tradition was still alive. The story revolves around a severed horse penis named Völsi (“phallus”) that is the focal point in the ritual.

The Völsa tale tells about an old man and an old woman who lived with their son and daughter on a promontory far from other people. A slave and a slave woman also lived on the farm.

When the slave had slaughtered the horse and was about to discard the penis, the son came by. He took the penis to his mother, who was sitting with his sister and their slave woman.

The boy teased the slave woman that “the member would not be boring between her legs”, and the slave woman laughed. That this was not completely accepted is indicated by the reaction of the daughter, who asked her brother to get rid of the penis.

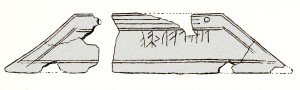

Bone knife with runes found in a grave in Fløksand in northern Hordaland county, Norway. The inscription reads: lina laukaRa. In ancient folklore onion was a protection against disease and spells. The runes on the blade were probably spoken in a phallic ritual. Illustration: NIæR, Norges Innskrifter med de ældre Runer (Inscriptions in the Elder Futhark)

But the mother, described as a great song woman, kept it and thought it would be useful. She packed it into a linen kerchief along with onions and herbs to preserve it. Every night the woman took the horse penis out of the wooden box, and the whole household took part in a ceremony where she recited a rhyme, gave the penis to her husband who did the same, and then on to the next person until all had taken part in the ritual.

Female graves

Wrapping of the penis in linen and onion is a known ancient tradition. A meat knife from the 300s CE, found in a woman’s grave in Fløksand in northern Hordaland county, has a runic inscription which reads: lina laukaR(a) ‘flax onions’. Lauk is also known from other Old Scandinavian inscriptions.

For example, it appears on a gold bracteate (a flat, thin, single-sided embossed metal plate worn as jewelry) from Skrydstrup in southern Denmark. Another one, from Skåne in southern Sweden, was deciphered by Sophus Bugge: “You have become powerful, Volse! and (now) taken up (out of the coffin), furnished (as you are) with linen and propped up with onion. M–receive this offering, but you, farmer, take hold of Volse!”

Several stone phalluses have been found on or in female graves. We may ask what role a male fertility symbol plays in a woman’s grave? The answer may be that stone phalluses had more of a general fertility role, where the main interest was not a physical sexual act, but rather encompassed all growth in nature. And the Völsa tale, where the lady of the house led the ritual, may indicate that women had a leading role in the phallic cult.

But how can we explain the more peripheral stone phalluses that were not connected to graves, house sites or ancient shrines? These locations may indicate that people held annual processions, bearing their fertility symbols through the agricultural landscape—a blessing round where stone phalluses were carried around to bring a good year and peace.

Holy stones

The word “phallus” has its origins in the Greek phallos. The word was later adopted in many modern languages and refers to the more common word penis. Objects that visually resemble a penis or act as a symbol for it are more correctly referred to as having a “phallic” shape.

Stone phallus in white marble found at Kvernes stave church in Averøy in Møre og Romsdal county, Norway. Photo: Åge Hojem, NTNU University Museum.

The phenomenon of “sacred stones” can possibly be traced back to the stone at Bethel, which is mentioned in the Bible. It is linked to the Canaanite god Baal and the story of Jacob, who was resting his head on a rock there when he saw a vision of a ladder to heaven.

Sacred stones were perceived as a connection between the human world and that of the gods, and were thus regarded as shrines.

Archaeologically, this group of finds goes by the name “sacred white stones.” Most are made of white quartz or marble. These stones have been associated with burial sites, where several of them have been found, while others do not seem to have been associated with a grave.

Nevertheless, we assume that they were an important part of a cult, where they played a central role in the rituals related to fertility cultivation. Several of the phallic stones are found at churches and ancient church sites. This suggests that the rocks represent a continuous location for worship, where a pagan cult existed before the place continued as a church.

Why white?

Archaeologist Th. Petersen was the first to describe these as “sacred white stones”, alluding to the light marble they were usually made of.

The white colour has had special significance, also in Scandinavian mythology, where white is perceived as representing the transcendent. The Poetic Edda poem Gudrunkvadet refers to “taking the oath by the white sacred stone”. The white phallic stones are reminiscent of a holy altar, where it would have been natural to swear the oath.

It does not seem to be coincidental that most stone phalluses are white. Linguistically, the word white has arisen from Greek leukos,’light’. The white colour symbolizes ritual purity and wisdom – but also death.

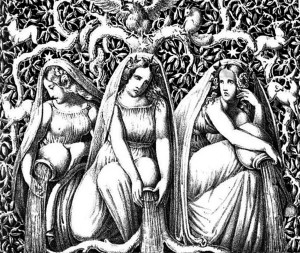

Urd, Verdande and Skuld, also called Norns in Norse mythology, are the three goddesses of destiny. They sit in Åsgård at the roots of the world tree Yggdrasil. One of their tasks is to pour white sand over the tree roots. Illustration: Die Helden und Götter des Nordens, oder Das Buch der Sagen. G. Gropius

In many cultures, white is the colour of priestly attire. Celtic druids were dressed in white, Egyptian pharaohs had white crowns, and Persians believed all gods were dressed in white. These examples all tie the colour to the divine.

The Poetic Edda poem Völuspá mentions white sand that is scooped up from Urd’s well and poured over the tree Yggdrasil, and in the Prose Edda story The Tricking of Gylfi, author Snorri Sturluson says that the sand that the Norns pour over the tree every day is so sacred that everything that reaches the bottom is as white as the membrane within an eggshell.

This portrayal of white sand, or water, that is poured over the tree points to fruitful and life-giving powers that sustain the cosmic principle.

In this way, phallus stones may have helped to create a cosmic connection. They served as a protection for the deceased and for the gravesite, but also strengthened the bond between the living and the dead, who still had their place in the family.

Deities

Many researchers have linked the sacred white stones to mythological analogies and tried to see them in the context of a fertility deity. Frey, Freya and Njord are the foremost of these in Norse mythology.

The historian Tacitus from 100 CE writes about the female deity Nerthus. Scientists later linked her to the Vanir god Njord, because etymologically Nerthus may have evolved to Njord, who might have been an androgynous deity.

Germanic tribes thought that Nerthus lived on an island in a sacred grove. In this grove there was a consecrated carriage covered by a blanket.

The priest was the only one who was allowed to touch the carriage. He knew when the goddess was present and followed her with great reverence when cows would pull her carriage. The places she honoured with a visit were celebrated with festive feasting. At these times nobody went to war or bore arms.

Maybe sacred stones were located where the deity’s procession stopped and performed rituals, with the stone as the focal point. Many stone phalluses have been found in graves, and that is probably why some have interpreted female graves with stone phalluses as goddesses’ tombs. Women were the leaders of a female-based fertility cult.

A special discovery

A very special Norwegian find from Høgberget in Skatval, Nord-Trøndelag county suggests that this may be a cult shrine, including traces of the rituals associated with a phallic cult. Here, on top of a crag, a stone phallus in a water-filled pit was discovered.

The pit was regularly shaped, filled with water, and over one meter deep. Next to the stone phallus lay several oblong marble tiles with a maximum length of 0.74 centimetres. The tiles may have been taken from a marble passage on the north side of Høgberget, approximately 150 metres from the water-filled pit.

Archaeologist Sverre Marstrander saw the pit as Mother Earth’s vulva and the white marble stones as semen entering the vulva—all as part of a magical fertility ceremony that would bring a good year and peace.

Life cycles

The phallus was a symbol of fertility, but it could also be included in a death cult. Sexuality and rebirth can be seen as a continuous cycle linked to the fertility that the stones seem to reveal. The phallus was a prestigious symbol.

Some consider the phallus to be a symbol of the god Heimdall, who in Norse mythology is one of those who will take the lead in the new world that occurs after the old one goes under in the apocalyptic Ragnarøk event.

Aud Beverfjord is the adviser at the Department of Archaeology and cultural history, NTNU Museum. This article was previously published on norark.no.