Can windmills and seabirds coexist?

Can offshore wind power be combined with good seabird management? Using GPS to track seabirds, a research project has come up with a surprising answer.

Many seabirds aren’t faring too well. Kittiwake populations, for example, have been plummeting in the last few decades.

Researchers have no clear answer as to why the seabirds are disappearing. However, dramatic changes in marine ecosystems have been recorded, which are affecting the seabirds’ access to feeding areas. These shifts may coincide with recent climate change.

Then there’s offshore wind power. This type of power generation is one of the fastest growing sources of renewable energy and has been expanding to marine areas. This creates concerns for possible negative effects on marine wildlife, especially seabirds. Will this power generation increase the seabird mortality by birds colliding with wind turbines? Will the wind turbines become a barrier in the birds’ migration routes or force the birds away from good feeding areas?

Signe Christensen-Dalsgaard has investigated these questions in her doctoral dissertation at NTNU. She has studied the kittiwake and common shag species, observing where they travel and find food, what they eat and how this affects their reproduction.

Her findings provide insights on how offshore wind power can be combined with good seabird management.

- You may also like: Uncovering the secrets of Arctic seabird colonies

Where is the bird’s food dish?

Scientists know a lot about seabirds while they reside in their nesting colonies. There it’s easy to record what they are doing. But when the birds are out searching for food, they are out of sight.

“Before now we haven’t known where they go or what they do,” says seabird scientist Christensen-Dalsgaard.

“Understanding the birds’ travels in time and space is important knowledge, both to know why populations change and to measure any conflicts between seabirds and human activity.

That is why Christensen-Dalsgaard chose to use GPS technology, which has come a long way in recent years. GPS trackers are now so small that they can be attached to seabirds. This allows researchers to record where the birds go when they leave the colony and what their important feeding areas are.

Article continues under photo.

Signe Christensen-Dalsgaard attached small GPS trackers with cloth tape to the back or tail of about 250 nesting shags and the same number of kittiwakes to record the birds’ movements. Photo: Signe Christensen-Dalsgaard

GPS on tail

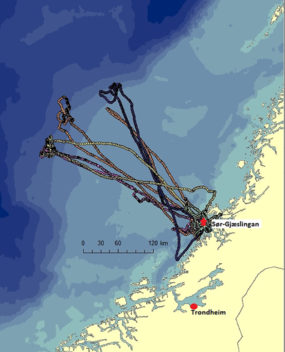

To chart the birds’ movements, Christensen-Dalsgaard taped small GPS trackers to the back or tail of about 250 nesting shags and the same number of kittiwakes, from selected colonies along the Norwegian coast.

After a few days, she gently captured the birds and removed the GPS trackers. The information from the GPS was downloaded to the computer.

She did this for four summers to acquire enough data on the birds’ behaviour.

“The birds do different things in the course of a season and in different years, so it’s important to follow a certain number of birds over a certain length of time,” she says.

The red-legged kittiwake is a small gull and is listed as a vulnerable species. Christensen-Dalsgaard studied the species in three places: at Sør-Gjæslingen in Trøndelag county, Anda in Nordland county and Hornøya in Finnmark county. The shags she studied were on the Sklinna islands in Trøndelag and on Hornøya.

- You may also like: Five kilometres between life and death

What governs the birds’ choices?

Christensen-Dalsgaard’s patient work has provided evidence of how the kittiwake and shag obtain their food. In addition, she learned why the birds go there, what governs their choices and what significance these choices have for the survival of their young.

She concludes in her doctoral thesis that it is possible to predict the areas that are important for nesting seabirds – and that are therefore also important to protect from human intervention such as offshore wind power.

Christensen-Dalsgaard found that the species she studied were flexible as to where they got their food, and they had the ability to switch between different feeding areas when available.

It is important to follow a certain number of birds over a certain period of time. The photo shows a kittiwake. Photo: Signe Christensen-Dalsgaard

“This makes them adaptable to changes in the marine environment as long as they have access to alternative feeding grounds,” the researcher says.

Side by side is possible

“So, for the two seabird species I studied, the results show that given thoughtful and knowledge-based management of the marine areas, we can probably establish offshore wind power without serious damage to their populations,” she says.

But the researcher also stresses that it’s critical to think about and investigate the placement of wind farms case by case. She points out that there is a big difference between the consequences of a few turbines or a small wind farm and a facility consisting of several hundred or thousands of wind turbines.