Boys still lag behind in reading

When boys start school, they recognise fewer letters and their corresponding sounds than girls do. The difference is just as great at the end of the school year.

From their first day in school, boys’ reading proficiency in Norway is on average much worse than that of girls. And it doesn’t appear that this discrepancy levels out during the first school year.

“The fact that that the discrepancies don’t diminish during the school year is a sign that we have to change how we teach letters and reading,” says Professor Hermundur Sigmundsson from NTNU’s Department of Psychology.

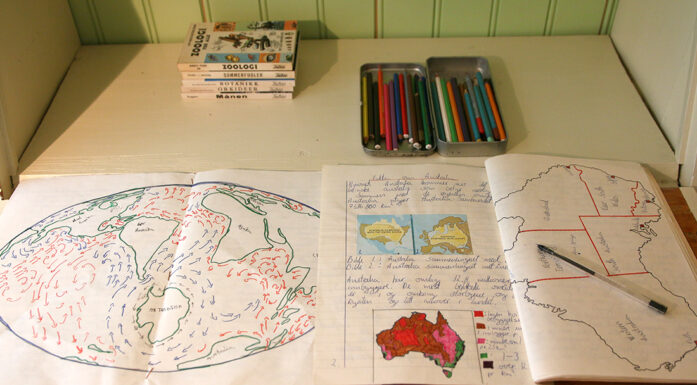

The letter-sound knowledge (LSK) test by Greta Storm Ofteland assesses children’s knowledge of capital and lowercase letter names and sounds. Photo: Colourbox

The study’s findings were recently published in the journal Frontiers in Psychology. The study followed 485 Norwegian children – 224 girls and 261 boys – aged 5 to 6 years through a school year. Participating children came from many different schools in one Norwegian county.

The Norwegian version of the letter-sound knowledge (LSK) test used for the assessment was developed by Greta Storm Ofteland, a special educator and teacher for 45 years. The test assesses how many capital and lowercase letter names and corresponding sounds a child knows.

- You may also like: What do we do with boys who can’t read?

Reading skills elude very fifth boy

Subject area gender differences are nothing new. Until recently, girls lagged way behind boys in maths, but the gender differences in this subject are beginning to level out in Norway, PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) results show. The problem is also completely different for the boys.

Most girls have a good foundation in mathematics, but they’re just not achieving the highest grades as often as boys. Boys’ reading problems are located at the other end of the proficiency scale, putting them at risk of falling through the cracks.

Among Norwegian 15-year-old boys, 21 percent are simply unable to read well enough to understand a text.

“According to the world’s foremost researchers in the field, this figure should normally be in the range of two to five per cent. Here we have a difference of 16 to 19 per cent that’s due to inadequate teaching. We can’t accept that,” says Sigmundsson.

- You might also like: Skill building the right way

Reading is key

Being able to read well is the foundation for success in basically every subject. That’s why it’s so important to help children read well as early as possible.

“If we don’t improve children’s reading skills, the problems can persist throughout the school year and even the rest of their lives,” says Sigmundsson.

Boys have lagged behind girls year after year. Over 50 000 primary school students in Norway receive special education, and 68 per cent of them are boys. Special education costs Norwegian society 12 000 FTE employees and several million euros each year.

Important to catch problems early

“The reasons the boys struggle more with reading are clearly linked to less practice and experience with it than girls. Reading is a skill and requires a lot of practice,” says Sigmundsson.

The boys in the study continued to trail the girls, even after receiving instruction for a whole school year. Better monitoring and follow-up are missing here.

“We can also assume that too little practice is happening at home. Parents carry a big responsibility for this too,” says Sigmundsson.

One problem is that students are no longer required to read as much at school as they used to. As a result, the least motivated readers basically read even less compared to children who already like to read. Motivation is often linked to mastery, so it’s important to prioritize reading the first two to three years of school.

“It’s a matter of catching problems early,” Sigmundsson says. He thinks many measures are implemented too late.

Experience and early stimulation are essential for developing these skills. In order to break the reading code, it is important to learn the letter names and their sounds before continuing on to learn words. This method is not mandatory in Norway. Sigmundsson believes it should be, and says that international research supports this approach.

Reference:

Gender gaps in letter-sound knowledge persist across the first school year. Hermundur Sigmundsson, Adrian Dybfest Eriksen, Greta S. Ofteland, Monika Haga. Frontiers in Psychology.