Name change in the United States brought economic payoff

Many immigrants changed their names when they came to the United States at the turn of the last century. People who changed their first names often landed better-paying jobs.

A significant proportion of immigrants chose to change their first names when they came to the United States. This is a part of family history for many Americans, but there has been little concrete research to support this popular assumption.

Now researchers have investigated and quantified the extent of the phenomenon. Their analysis shows that Americanizing one’s name was linked to better pay.

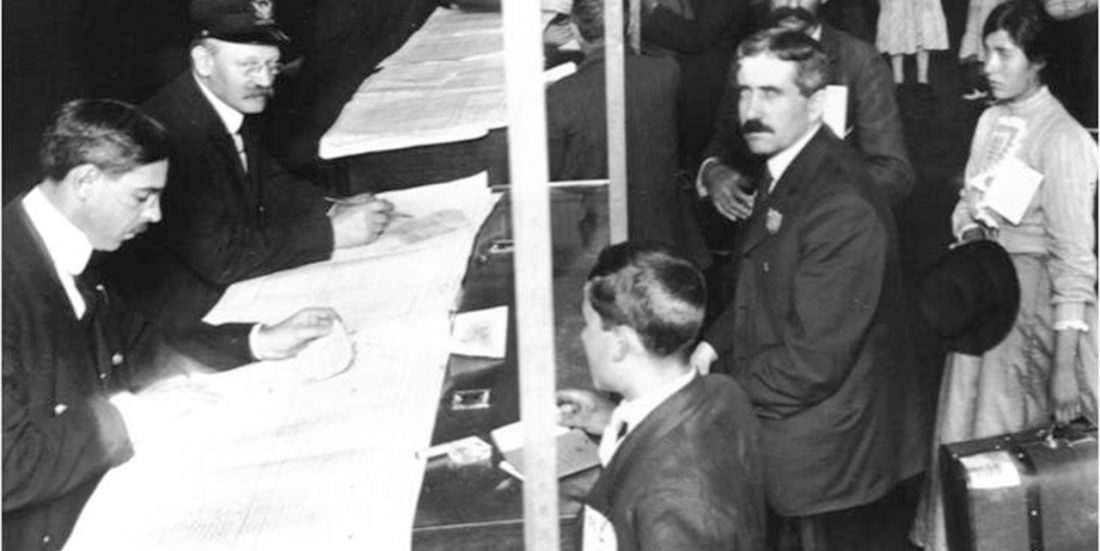

More than twelve million immigrants entered the United States from 1892 to 1954 through the portal of Ellis Island, a small island in New York Harbor. The picture shows the Registry Room, or Great Hall, where newly arrived immigrants were given physical exams and legal inspections. Photo: US National Park Service archives

“On average, immigrants who changed their first names earned about eight per cent more than those who didn’t,” says Costanza Biavaschi, an associate professor in NTNU’s Department of Economics.

And immigrants who arrived with the strangest sounding names and changed them to the most common English-sounding first names, were paid significantly more. A “John” could garner 22 per cent better earnings than a “Guido.”

- You might also like: Scandinavians shaped by several waves of immigration

Big differences

“Thirty-three percent of immigrants to the United States changed their given names within the first 10 years of their arrival,” said Biavaschi.

However, where people came from made a big difference. Immigrants who had strongly foreign-sounding names were much more likely to change them.

You probably wouldn’t change your name to John if it was already Jon. But if you came over as Giovanni – and even more so if you were Ivan or Elewfery – you’d be much more likely to Americanize it.

The researchers also found that Norwegians rarely changed their names when they came to the United States, but that people from Central Europe, Southern Europe and Eastern Europe more often would.

About 15 per cent of Norwegians chose to change their first names. But this is a small percentage compared to Russians, with almost 58 per cent changing their first names. Nearly 20 per cent of Italians opted for American versions of their first names. English and Irish immigrants almost never did.

Varied reasons

Two factors appear to have contributed to explain why people who changed their names on average ended up with better paying jobs.

Ellis Island, in New York Harbor, as immigrants would have seen it upon arrival (without the NPS sign). Photo: US National Park Service

One was that employers more often hired people with English-sounding names for higher positions.

The researchers believe that a change of name might have been more common among people who had no other alternatives for socio-economic improvement, to better integrate into their new country.

- You might also like: Norwegian journey, Vietnamese dreams

Research lacking

“One reason there is so little research on immigrants’ name changes is that there are almost no good sources,” says Biavaschi.

The researchers were able to use the responses of more than 4000 people who completed an application to become a US citizen in 1930. Most of them had come to their new homeland around 1918.

By that time, the great Norwegian migration wave at the end of the 19th century had largely ebbed, and former Norwegians who had assimilated well warmly welcomed those who came later. The newly arrived Norwegians may thus not have felt a need to change their names.

Biavaschi collaborated on her research with Corrado Giulietti at the University of Southampton and Zahra Siddique at the University of Bristol. The study was published in the Journal of Labor Economics.

Source:

Costanza Biavaschi, Corrado Giulietti, and Zahra Siddique, “The Economic Payoff of Name Americanization,” Journal of Labor Economics 35, no. 4 (October 2017): 1089-1116. https://doi.org/10.1086/692531